Sector-led advice on new and/or refined YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH models of care

Between January and June 2025, Orygen led a consortium of youth mental health organisations to provide advice to the Australian Government on the current system of mental health services for young people aged 12 to 25, and on potential new or refined youth mental health models of care. The work was commissioned by the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing (then the Department of Health and Aged Care).

The consortium that delivered this advice was made up of many of Australia’s leading youth mental health organisations including Orygen, batyr, Brain and Mind Centre (University of Sydney), headspace National, Mission Australia, ReachOut, SANE Australia, yourtown and Youth Focus, as well as subject matter and project management expertise from dandolopartners, Indigenous Professional Services Management Consultants, Department of General Practice and Primary Care (University of Melbourne), and Monash University Health Economics Group.

The final reports are now available:

Who we spoke to

Nationwide consultations with key stakeholders in youth mental health were held from April to June in 2025, including dedicated consultations to prioritise the voices and experiences of young people across Australia, their families, carers and supporters, and First Nations organisations.

This helped us understand how the youth mental health system is currently working and what needed to change to improve the experiences and outcomes for young people and those who support them.

We spoke with 544 people in total, including 146 young people, 70 parents, carers and supporters and 328 people across 294 organisations including service providers, community organisations, peak and professional bodies and government.

Stakeholder engagement by type

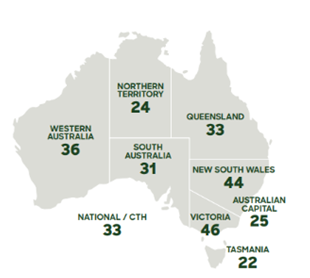

BREAKDOWN OF SECTOR/ORGANISATION ENGAGEMENT BY STATE/TERRITORY

Orygen would like to acknowledge the work of batyr in facilitating broad youth engagement and Indigenous Professional Services (IPS) Management Consultants for First Nations engagement.

Orygen and all members of the consortium extend their deep appreciation to everyone who participated in the project and shared their time, experiences and expertise.

What we heard

- There are already good examples of youth focused models, including those that provide a warm entry point such as headspace, and that involve lived experience workers, build mental health literacy, and education initiatives and resources to enhance student wellbeing in schools.

- Young people want person-centred, inclusive, and community-grounded models of care. They want the social determinants of poor mental health to be addressed and more investment in a diverse, trauma-informed workforce that is enriched by lived experience.

- Families want a system that’s easier to navigate, ‘supports the supporters’ and responds to their diverse backgrounds. It is difficult and confusing to find information about what services are available, where, to who, and how to access them. They want services to connect better and wrap support around their young person – not one that makes them jump through hoops to access care.

- There is a ‘missing middle’ in the system, particularly for young people with more serious and complex mental health issues. Services are responding to historic levels of demand and are under increasing pressure to determine eligibility for care as quickly as possible. However, too often early screening and assessments focused on clinical criteria, risk thresholds and diagnosis had become another service barrier or a tool for service exclusion.

- Workforce concerns are everywhere. Around the country, services find it difficult to attract staff. But it’s particularly acute in rural and remote areas, where local communities, networks and schools are the frontline responders to youth mental health and youth suicide.

- There is a need to strengthen the focus on prevention and mental health promotion and support points of connection to young people within the community.

- Services want to work together, but stronger service integration requires dedicated resourcing, skills and systems better designed to support people working together.

- Families, carers and supporters are a critically important part of a young person’s mental health care team. Models of care need to not only recognize this, but resource and support meaningful family engagement in care, and provide support to family members who are impacted by their young person’s mental ill-health.

- Current models of youth mental health care are not always appropriate, effective or accessible for some young people and their families/kin/mob, including but not limited to First Nations young people, multicultural young people, and young people who have experienced trauma in health settings or other service settings.

- There was support for leveraging digital technologies in practice and service delivery but that it should be integrated with face-to-face services – or provided as an option for young people, not a substitution for receiving care in person.

What we said about new and/or refined models of youth mental health care

New services and/or service approaches are needed to fill the gap for young people who are missing out on care, particularly because they are seen as too difficult to reach, too complex and/or too risky to support. These young people need services that prioritise them in their design and delivery.

The advice recommended new and refined models of care and included additional focus on developing specifications and implementation considerations for the expanded and new youth mental health services that were committed to by the Government in the 2025 election.

The models presented included:

- An enhanced headspace model with greater capacity to support young people, including those presenting with more complex mental health needs. This includes assessment, delivery of medical and psychological interventions and a broader range of integrated psychosocial supports. Key features would include:

- no referral

- extended hours

- expanded outreach efforts

- offering flexible care options like drop-in services and Single Session Therapy (SST).

- A new youth specialist service model to more comprehensively address the ‘missing middle’ of the system and deliver multidisciplinary care for the upper end of moderate to severe, persistent and complex clinical presentations (across all diagnoses) and intensive case management to support social and functional recovery. Key features would include:

- Secure long-term tenure of care

- Specialist care streams for specific mental health conditions e.g. eating disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, early psychosis, PTSD, and substance use disorders

- Assertive outreach teams and strong partnerships

- Comprehensive and fully integrated psychosocial support.

- Community youth wellbeing hubs that have a stronger emphasis on cultural and/or community connection, social and emotional wellbeing, peer-led and peer-based services, and relational engagement and support. Key features would include:

- Peer workers and community mentors as the core workforce

- No referral, open predominantly after school and regular business hours and offers general counselling, creative and nature-based programs, social groups, and family support

- Practical support such as access to everyday essentials (food, Wi-Fi, safe spaces).

The advice also recognised that for existing service models, and any new or refined ones, there are several enabling factors that are crucial to improving the youth mental health system. These include (but are not limited to):

Psychosocial support must be fully integrated and funded within youth mental health services and be considered an essential component of evidence-based high quality clinical care. This includes wraparound supports such as vocational and educational support, housing support, life skills, group programs and community engagement.

We need improved access to information on current and future youth mental health services. Policy makers, funders, researchers, service planners and, most importantly, young people and their families, carers and supporters all need to know: what’s available and where; who it is supporting; what they should expect from the service; and what outcomes the services are delivering.

We need youth mental health services powered by continuous improvement and evidence. The advice proposes a learning health system approach to youth mental health care, bringing together data, experiences of implementation in real time, connected to research and regularly translated into policy advice, workforce development, system design and service adaptation. At the heart of the learning system should be engagement with young people, so they can say what is working for them and what isn’t.

Full copies of the reports